by Danielle LongIn chapter 8 Kathryn Bouskill approaches how using humor is a way of coping with something (and in the case the painful and emotional disease of breast cancer). On page 213-214 Bouskill argues that humor is a cognitive, that it is internal reworking of a greater sociocultural reality, with neuroanthropology being the center element. The reason scientifically humor is a meaningful coping device because of it functioning in two directions of sociocultural and the interaction of cognition.

The humor element usually takes place with the survivors because it helps them be more open with others who are facing the same things they did and it also helps them start accepting the disease. The survivors of breast cancer in our country are labeled as both socially and medically for the rest of the lives- meaning that the disease affects the key signifiers of the female identity. On page 215 Bouskill defines coping as “the behavioral and cognitive means of managing a stressor that is perceived as exceeding one’s resources or blocking one’s path toward a desired goal.” Coping can be a great resource in dealing with something like breast cancer but the ability and effectiveness of coping with a disease are never unbounded from the sociocultural contexts. This means that personal relationships (having conservations with familiar and unfamiliar people), spiritual ideas (like religion), where do you fit in the social ethnicity, having access to institutional support, and when the illness/disease or condition is denounced- making all of these reasons difficult. The coping process is cognitive and it belongs to sociocultural environment. And with the brain in the perception of humor, then sociocultural contexts are the necessary spark. Abel describes humor on page 216 “as a coping strategy within which there is a cognitive-affective shift and a restructuring of a stressful situation to make it less threatening.” With his description makes sense why we turn towards humor while dealing with stressful events in our lives and his statement is very interesting as well. While we respond to humor it is complexed and we have to rely on focus, attention, memory, emotional evolution, and understanding abstract communication. Goldstein shows how powerful humor is as a cohesive force with defining relationships. Humor also demonstrates a consciousness of solidarity and a shared social identity. The boundaries that humor produces from the people who understand humor and the ones who do not can be from linguistic differences, social, classes, and different social identities. Bouskill tells us about “cancer world” and how drastic the physical transformations incurred by the loss of signifiers of femininity. They also worry about relationship changes with a partner, the future of one’s family, the frustration of memory loss due to chemotherapy and the fatigue-ness by chemotherapy. There are quotes from survivors that show the positive effects of humor, for example: “laughter lets me get out of this fear. It brings me peace, it’s a stress-reliever, and I just go off to another place.” Because of laughter this cognitive element of humor activates reward centers in the brain. Another positive effect of humor is the women who use it to cope with stressful events have lower blood pressure than women who don’t. Humor among women have more personal social connections and sensitivity- meaning this leads to women having more to empathy. Humor can relieve any tension caused by stressful situations. Bouskill’s information that she provides in this chapter on how affected humor actually is by an neuroanthropology outlook is very interesting. Humor can produce laughter which activates rewards in the brain and it can also reduced blood pressure. Humor is a way of coping with something like breast cancer and can help you in accepting the disease. And humor as a coping device relies on sociocultural and the interaction of cognition. Bouskill, L. (2012). Holistic Humor: Coping with Breast Cancer. In Lende, D. H & Downey, G. Eds. The Encultured Brain: An Introduction to Neuroanthropology. (pp. 213-235). Cambridge, Massachusets: MIT Press.

14 Comments

by Kelly LikosM. Cameron Hay comparatively discusses Sasak medical cultures and American medical cultures in Chapter 5: Memory and Medicine. The questions studied through out the comparative study revolves around the connection between medical assumptions and the active use of memory. Additionally, Hay attempts to argue three points within the chapter: that memory and medicine must work together within contexts, that these interactions must take place within the sociocultural locations of the world, and that we must strive to stop separating biological sciences from the social sciences.

Hay references Budson & Price (2005) and Squire (2004), who describe memory as “a collection process embedded within or, more accurately, catalyzed by specific brain structures”. Four brain structures are thought to be vital to the memorization of medical traditions. Hay goes in depth to define episodic, semantic, procedural, and working memory. Particularly episodic and semantic memory are described as “explicit and declarative”. Hay believes that there is a relationship between environmental influences and the biocultural style of learning. Hay hopes to show this through the comparative look at Sask medical education and American medical education. The Sasak ethnic group commonly lives on the Island of Lombok, which is known for it’s abundance of small hamlets and poor health. Jampi is the exclusive set of medical concepts used by a majority of Sasak people. Biomedicine is not believed by the Sasak to be a form healing. Therefore, many do not seek help from a clinic unless they have already attempted jampi treatments. Jampi is passed down verbatim through family lines. It is believed that if more people than necessary know jampi, it leads to a weakening of the healing properties. To contrast the Sasak, who rely solely on a set of memories to provide medical treatment, Hay dives into the set of knowledge composed into American medical traditions. Hay notes the common assumptions of American medical education: competent medical practice is scientifically based, scientific knowledge is wrong and can always be improved, and that scientific knowledge should be integrated into one’s already existent knowledge. Schemas are a common and encouraged tool when attempting to memorize many different forms of information. Schemas allow for new knowledge to be assimilated efficiently into categories and allow for selective forgetting that has the ability to be independent from hippocampal stimulation. Interestingly, Hay speaks extensively on the role of the hippocampus. The hippocampus facilitates memory consolidation and memory plasticity. Recalling information that has been placed into categorical schemas requires plasticity to facilitate the movement between varying schemas. In relation, the amygdala is responsible for “mediating both biological and emotional stress by focusing on various brain structures to gather memories in order to resolve the stressor”. In American medical traditions, anxiety is associated with not being able to recall information, or in this case, a particular unfamiliar illness. Sasak healers utilizing jampi use schemas that have primarily social reinforcement and must be precisely associated with symptom cues. In contrast, American healers work primarily with core knowledge which can be integrated into other aspects of medical care. American healers must retain the ability to change information in their minds as new knowledge is gained. Through the different ways the Sasak healers and American healers encode medical knowledge, we began to see the larger problem of knowing what information to utilize at what time. This is troubling when healers must actively take in information concerning symptoms and associate them with particular illness. Memory plasticity is a necessity. Hay’s chapter provides a detailed and fascinating learning contradiction between two strikingly diverse cultures. The formation of schemas and the ability to move between them permits for a beautiful insight into the ever-changing knowledge surrounding neuroplasticity. More profound differential examples, like the Sasak, would allow for an even greater understanding of memory and how it shapes cultural traditions. This is a particularly interesting case study under the field of neuroanthropology. Memories and traditions, paired with neurological function allow for potentially great window into new neuroanthropolgical knowledge. Lende, Daniel H.; Downey, Greg (2012-08-24). The Encultured Brain: An Introduction to Neuroanthropology (141-167). The MIT Press. by Mirjam HollemanThis article explores the links between humor, communication (including intrapersonal communication), and resilience, through anecdotal account of Vietnamese prisoners of war (VPOWs) who used humor as “a tool for building relationships and a weapon for fighting back” (p. 85). Using ‘put-down’ forms of humor, the prisoners would joke about, or try to trick, their captors. This enhanced their personal sense of control and provided them with humorous anecdotes with which to buoy each other up and strengthen their social network. Twenty years after their release, the incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among these men was no greater than among the general population. This finding was remarkable because, previously, a diagnosis of PTSD was received by between 50 and 90 percent of POWs. In her article, Henman (2001) clearly illustrated the “VPOWs effective communication and their advanced and heightened sense of humor” (84) as contributing factors to their resilience despite arduous circumstances. Humor is described as a lubricant to communication, especially during trying times, as well as an aid in effective adaptation or adjustment to circumstances, while adaptability is defined as a “primary component of resilience” (p. 85), thus portraying the interconnectivity between humor, communication, coping, and resilience. As many of the respondents experienced periods (lasting a few days up to several years) of solitary confinement, humor and communication is approached from both an intrapersonal (within self) and interpersonal perspective. Humor is seen as a way of redefining a situation, “making light of the intolerable” (p. 87), and imagination comes into play in several of the anecdotes. For example: While in solitary, Venanzi (one of the prisoners) created an imaginary companion, a chimpanzee named Barney Google. The chimpanzee often accompanied Venanzi to interrogation and served as his voice for insults and criticism [directed at the guards]. Frequently, Venanzi would address comments to the imaginary companion and react to Barney’s retorts. On occasion, the guards would ask what the chimp had said. […] Venanzi’s ability to mock the guards [through Barney Google] and to draw them into the ruse served as fodder for many humorous stories among the VPOWS”(p. 91). In conclusion, the VPOWs experiences provide a poignant lesson in the use of “humor to restore one’s perspective, [provide a some sense of control], and to build rapport and connection with others” (p.93)

This article aligns well with the reading for today, especially Kathryin Bouskill’s chapter Holistic Humor: Coping with breast cancer, which presents humor and coping from a neuroanthropological perspective, as a communicative skill that has the power to transform and transcend a situation. “That which is threatening [can be] projected as humorous” (p. 225), with the accompanying positive emotions of defiance and resilience, brought about by the activation of “neurological centers of positive emotion” in the brain (p. 228). A neuroanthropological approach adds to both anthropological/anecdotal accounts of how humor has helped people cope in the most stressful of circumstances - by also showing the “physiological depths of humor as a coping strategy” (p.228) - as well as to neurological studies of humor and the brain by explaining how “ the activation of neuralological reward centers […] is inherently bound up in socialcultural contexts, social interactions, and personal meaning making […] to reduce humor to a hard-wired neurological reward system would undermine the socially meaningful experience of humor among the breast cancer survivors” [and POWS] (p. 228). Humor both reflects a cognitive shift in perception and induces it, by the ability to redefine a situation [through intrapersonal and interpersonal communication] and realigning neural pathways. This humorous scene from my favorite movie “La vita é Bella” (life is beautiful), clearly illustrates “the value of a kind of thumbing one’s nose at an unspeakable or frightening situation” (Henman 2001:87) Henman, L. D. (2001). Humor as a coping mechanism: lessons from POWs. Humor, 14(1), 81-94. Bouskill, L. (2012). Holistic Humor: Coping with Breast Cancer. In Lende, D. H & Downey, G. Eds. The Encultured Brain: An Introduction to Neuroanthropology. (pp. 213-235). Cambridge, Massachusets: MIT Press. A Review of "From Habits of Doing to Habits of Feeling: Skill Acquisition in Taijutsu Practice"2/17/2016 by Mike JonesKatja Pettinen’s case study on skill acquisition follows the training and teaching philosophies of Taijutsu practitioners mostly focusing around the premise that Taijutsu cannot simply be taught through repetition, it must be taught through feeling and what this means for skill acquisition in humans. The first section of the piece goes into great detail about all aspects of Taijutsu including full descriptions of proper technique in the art and personal stories about her time learning and practicing the art. At the end of the section, she mentions one of her main points tying together her argument being the sakki test which emphasizes the usage of feeling and sensing over doing.

The sakki test is the test one must take to be certified as a teacher of Taijutsu taken upon the attaining of fifth dan black belt and is described as “avoiding a single non-metal sword swing, a cut straight down that is performed behind the testee while he or she is kneeling in a seiza posture (sitting with the legs folded underneath the body)”. The ranking system of American Taijutsu and significance of this test are more deeply defined starting in the second section of the chapter. Pettinen proposes two possibilities for the stimuli that people feel in order to avoid the blade replacing the need for sight, but she goes on to say that it is unimportant what it is they are feeling the importance is in the fact that they are feeling it. She then directly states here that “the sakki does not require any action that repetition alone could achieve. Instead, it presents a form of sensory acuity that directly challenges cumulative notions of learning by highlighting feeling over doing”. Pettinen’s argument for this thinking over doing aspect of learning is a bit weak to me. She speaks of how moving away from the “vision-centered paradigm” of reaction suddenly becomes a completely different way of reacting to a situation. It is possible I do not understand some of the intricacies of Taijutsu, but personally I do not believe that perceiving through sound or slight feeling of the test givers movements behind them is any different than seeing them swing the sword at the “testee” in front of them. Vision may be a primary sense for most people on this planet but it is still just one of the many ways we perceive the outside world. I see the information presented more as a way to show the advanced transference of reaction from a visual stimulus to that of a touch or auditory sensation learned through the training of Taijutsu. by Molly JaworskiHave you ever tried standing still with your eyes closed and feel your body sway back and forth? Or participate in a sport that requires balance? In this chapter Downey discusses the enculturation of the human sensory system utilizing human physiology and neurology in combination with cultural training practices. Downey argues that skill formation such as balance equilibrium can affect the nonconscious motor systems through analysis of Capoeira as well as gymnastics. Tim Ingold, as stated by Downey, points out that attempts to understand embodiment in anthropology typically overlook “organic dimensions of enculturation” such as neurological adaption, indicating a need for recognition of biology in cultural anthropology (Location 3730).

Downey views the equilibrium system as a primary subject in the study of enculturation of the brain because it is a multifaceted system and it is a prime example of the plasticity of the human brain. The equilibrium system, though typically and unconscious or only semiconscious motor system, is something that can be ‘taught’ or ‘molded’ in order to adapt to certain cultural contexts. Balance is the topic of focus in this chapter and balance can be taught, improved, or changed according not only to physiological changes but cultural changes as well. The human equilibrium system has the ability to find multiple solutions for balance problems physiologically; for example heightened sense of hearing in the blind; as well as taught culturally like the heightened sense of balance in gymnasts and participants of Capoeira. What I found most interesting about this chapter is the how complex balance truly is. Downey states “standing upright is like balancing an inherently unstable inverted pendulum” and that in order to find that sense of equilibrium and balance, the human body is constantly shifting to counteract the natural sway of the ‘pendulum’ (location 3742). Balancing in itself is complex naturally but this equilibrium system can change according to natural adaptions as well as what we ‘teach our bodies to do’. Participants in sports such as gymnastics and Capoeira have found ways to train their bodies to respond accordingly to balance changes. There is no one way to respond to balance and so the equilibrium system utilizes a multitude of pathways to respond to such changes that, in turn, can become ‘reflexive’ and normal to an individual. It’s interesting that a system that is inherently unconscious, or only semiconscious can be influenced to the point of a response being reflexive and ‘natural’ to an individual. References Lende, Daniel H.; Downey, Greg (2012-08-24). The Encultured Brain: An Introduction to Neuroanthropology (Kindle locations 3694- 4204). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition. by Edward QuinnOur readings this week focus on the embodied effects of training in specific subcultural contexts. A very interesting example of this phenomenon can be found among taxi drivers in London. Becoming a taxi driver in London is an arduous, 3-4 year process that is cognitively demanding. Taxi drivers must learn the spatial characteristics of an area within 6 miles of Charing Cross train station, which contains roughly 25,000 streets. Only about half of the people who set out to become a taxi driver in London typically complete the training and exams required for qualification.

The hippocampus is an area of the brain that is associated with memory formation and spatial navigation, so it is reasonable to infer that the hippocampus is a particularly important brain structure for a London taxi driver. Woollett and Maguire (2011) build on previous cross-sectional studies showing greater gray matter volume in the posterior hippocampi of taxi drivers compared to matched controls who were not taxi drivers. Using a longitudinal research design with two time points, the authors tested the hypothesis that what drives these observed differences in the hippocampus is the 3-4 year taxi driver training process of acquiring “The Knowledge” of London’s spatial characteristics. They started off with two groups at Time 1 (taxi driver trainees and matched controls) and ended with three groups at Time 2 (qualified taxi drivers, failed taxi trainees, and controls). The authors found confirmatory evidence for their hypothesis. Qualified taxi drivers showed increased gray matter volume in the posterior hippocampus compared to matched controls and the group of failed taxi trainees at Time 2. The longitudinal research design lends particular strength to these findings, and gives us a reasonable basis for inferring cause and effect. In addition, the authors show that qualified taxi drivers actually performed worse than the control group on a memory recall test of a complex figure at Time 2, but not at Time 1. This last point is interesting because it suggests that there may be a cost to cognitive specialization driven by culturally specific training regimens. The training regimes people subject themselves to enable adaptation to particular demands, and this is a good thing so long as the demands do not change. It may be the case that the structural changes associated with qualification as a taxi driver actually inhibited performance on a short term (30 minute) memory test. If this is the case, it would be interesting to further explore not only the strengths people are able to develop through intense training, but also what weaknesses come as a cost of that same training. From a neuroanthropological perspective, we might have predicted that the training regime of London taxi drivers might be embodied in the form of structural changes in the brain. While MRIs provide a method of testing this idea, it might be enhanced by doing the ethnography of a London taxi driver. It would be interesting to hear how a London taxi driver describes the training process, and ethnography may corroborate the findings of Woollett and Maguire (2011). Also, neuroanthropologists place great emphasis on the importance of environmental input for the developing brain, with less emphasis on adult plasticity. This study used groups of men with average ages of 35, 38, and 41, thus providing an example of plasticity in the brain long after development is complete. It is important to remember that enculturation of the nervous system does not end with development, as clearly demonstrated by the taxi drivers of London. Overall, this is a great article with interesting implications for neuroanthropology. The idea that training regimes come with not only adaptive benefits, but also costs is an idea that deserves to be further explored. In neuroanthropology, plasticity in adulthood seems to receive less attention than plasticity in developmental stages of the life course, but this study shows that plasticity can be important in adulthood as well. The longitudinal research design lends great strength to the evidence for the embodied effects of training to be a taxi driver in London, and neuroanthropologists might benefit greatly from implementation of strong research designs such as the one used by Woollett and Maguire (2011). Reference: Woollett, Katherine, and Eleanor A. Maguire. 2011. "Acquiring ‘the Knowledge’ of London's layout drives structural brain changes." Current Biology 21(24): 2109-2114. by Olivia DavisThe practical application of ideas can be difficult when attempting to combine two or more already existing scientific or theoretical perspectives. The relatively new interdisciplinary field, Neuroanthropology, falls into this category of “okay, but what do with all of this information?” Christopher D. Lynn et al. discuss in their article, “Engaging Undergraduates through Neuroanthropological Research,” the University of Alabama’s application of neuroanthropological methods in research and has begun to use a neuroanthropological perspective in some studies that might have otherwise remained divided between fields (2014). The Human Behavioral Ecology Research Group (HBERG) is a group of undergraduate and graduate students at UA who are involved in multiple research projects, each in a different stage of completion, that take place over a year’s span to give them an idea of what life in the academic research community is like and prepare them for research in grander academia. This research initiative provides a platform where neuroanthropological approaches to research can be utilized at the undergraduate and graduate levels as well as contribute to the growing literature of the field.

Due to its origin in the Anthropology department at the University, HBERG’s research begins with an ethnographic approach and then moves into a more neurological research focus. Personally, I believe that this could be a beneficial sequence of events when it comes to incorporating anthropology and neurology into a research method because it evokes a relationship with the very people that could be hooked up to machines in the lab later on in the study. The type of understanding and trust that accompanies an ethnographer and a research participant in the field could potentially reduce the issue of a power dynamic when moved to a laboratory setting. There are, however, some less expensive and less invasive methods can be carried into the field but they come at somewhat of a cost in accuracy. As addressed in the article, these on-the-go neuroanthropological methods “compromise some precision” in terms of results. However, the trade-off may be worth the slight decrease in precision because these less complex methods allow for a more accessible neuroscience in the ethnographic field and provide an easily digestible pedagogy for both professors and future students who are interested in Neuroanthropology. One thing that I found particularly compelling about the methodology utilized by HBERG members at the University of Alabama is their creation and use of a workbook to standardize each research project. Having an organized research process is vital to the importance of the information gathered and also to its presentation to the scientific community, which is dependent upon one’s ability to decipher the fieldwork. The workbook acts as a syllabus, providing a list of goals that need to be accomplished within a certain timeframe and provides instruction and references for the researcher as they come across new things in the field. These workbooks also provide a dynamic outline of what the research should look like without restraining the researcher’s own data collection process and acts as an “active document” that can be referred back to for any reason in the research process (2014). This sort of organization and preparedness is exactly what neuroanthropological methodology needs in order to properly and accurately begin in terms of research and data collection. Works Cited: Lynn, C. D., Stein, M. J., & Bishop, A. P. (2014). Engaging Undergraduates through Neuroanthropological Research. Anthropology Now, 6(1), 92-103. by Isaac DismukeBy discussing common interests and goals of cultural neuroscience and anthropology, Seligman and Brown successfully argue for the mutual integration of these two fields which have historically not engaged one another. Such a combination can potentially provide both biology and social sciences with a more robust understanding of our human brains and their relationship to the environment, especially the socio-culture environment. The article emphasizes a recent point of commonality between cultural neuroscience and anthropology, specifically on the theme of embodiment. Embodiment deals with how the socio-cultural environment influences both behavior as well as structure of the nervous system. This notion could prove to be the foundation for an interconnected study of these once segregated fields.

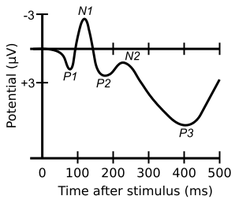

Neurobiology often attempts to identify and explain the bases of cognitive processes without taking into account the role that the socio-environment occupied in the evolution of the brain. This creates the possibility, if not probability, of biological reductionism. The article points to a salient factor to consider when studying cognition that perhaps neuroscience does not take in to account, which is the idea that not all cognitive processes will necessarily look the same in every context simply because all humans possess them. Neuroscience remains the predominant field for studying neural pathways and the underlying mechanisms by which they operate, but yet it may result in a more static response. Cultural neuroscience, however, seeks an ecologically sound explanation by considering the significance of culture and sociality in the forming of these cognitive and neural processes and the differences between them. The article points out the excellent position that anthropology is in to compliment cultural neuroscientific studies because of its historical focus with regards to studying culture. As the authors state, “Anthropology is positioned to make important contributions to the project of investigating culture in the brain, and the brain in culture” (p.130). Not only is culture important in the creating of social environments, but this social environment in turn influences the structure of the human brain. If this is true, and the evidence is quite suggestive, then ethnography based anthropology can be beneficial by supplying a more nuanced understanding of this process. Cultural neuroscience and anthropology obviously have an overlap in interests, but what are the direct benefits of a union of anthropology with cultural neuroscience? The authors state that the contribution from anthropology should derive from ethnographic data gathered about a culture in order to create a hypothesis that helps “push beyond identification of the neural substrates associated with isolated cognitive tasks, and better capture the contingent and socially embedded nature of human cognition” (p.131). Anthropology grants a more dynamic understanding of what is happening than a reductionist biological explanation and better captures the relevant social factors of human cognition. Furthermore, anthropologists, because of a more thorough cross-cultural knowledge, will aid in pointing out experimental design flaws that may exist because of cultural biases that otherwise may not be noticed. Using anthropological insight can be useful in advising neuroscientific experimental methodology. The subsection titled “common ground and complementary tools” traces a study on stress and emotional reactivity among Mexican immigrants in the United States, which found to have a translation problem regarding ‘social stresses’ or ‘trauma’ amongst the subjects of Mexican origin. They were given a math task and tested at public speaking in order to test the degree of stress amongst the individuals. The original study did not take into account the fact that highly educated adults, who were not amongst their immigrant population, may not experience the same amount of stress with these tests. After the realization of this issue, the authors had to change the design of the experiment which highlights the importance of “experimental manipulation [that] should also be subject to checks for conceptual and technical validity” (p132). The idea of an ethnographically-driven laboratory study and capitalizing on cultural knowledge from anthropology in order to create ecologically solid experiments does not appear to me to be a controversial one. In fact, it even seems necessary if the goal is to capture the complexity of human experience and study it in a laboratory setting. But the authors also propose the opposite stating, “The incorporation of proxy measures of central nervous system activity into ethnographically driven field-based research” (p 135). This idea seems more likely to be critiqued, and while the authors admit that in certain context this could be difficult, they also provide a concrete example of how it can be done. While studying religious practice and sprit possession in Northeastern Brazil, they measured in situ the emotional properties of various rituals by measuring physiological responses such as heart rate and blood pressure. This approach provided the author with a better understanding of the effect of ritualistic behavior on the human body that is beyond what simple observational ethnography would be able to provide. The article quotes Ochsner and Lieberman( 2001) who argue that the overall goal of a socio-culturally informed neuroscience should be “ to move beyond mapping, to the investigation of complex human behaviors and experiences”( 132). In my opinion this goal must be met with a neuro anthropological perspective that considers neural, ecological, and cultural factors. The article lays out this approach and argues for not only the influence on ethnography in the laboratory setting, but also field research to be complemented by laboratory studies by way of portable measurement devices. This calls for a combination in both theoretical and methodical approaches from anthropology and cultural neuroscience to provide a more rich understanding of the human brain as it is situated in its socio-environmental context. Rebecca Seligman, and Ryan A. Brown (2009). Theory and method at the intersection of anthropology and cultural neuroscience. Oxford University Press. Doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp032. by April Irwin In one of the most reader-friendly articles I have read about event-related potentials (ERPs), Tavakoli and Campbell (2015) explain what ERPs are, how they are used to make inferences about the brain, and give many methodological insights into how this particular type of brain data is collected and used. I chose this article with consideration of our discussions about how to successfully navigate the interdisciplinary gap between neuroscience and anthropology.

Tavakoli and Campbell describe ERPs as, “a change in the ongoing electrical activity of the brain associated with either an external physical stimulus or an internal psychological ‘event’” (2015, p. 89). ERP components are the positive and negative deflections that can be seen in the ERP form. Exogenous, or sensory evoked components, are sensitive to the physical properties of a stimulus while the endogenous, or cognitively evoked components, are subject to more psychological properties such as decision-making or meaningfulness. We generally know more about the sources of the exogenous components, but are still working on being able to isolate the general causes of the various endogenous components. Understanding the cultural and social contexts in which these exogenous components occur would be a great way to put this method to use in the field, especially if we’re thinking about cross-cultural anthropology. Perhaps the sociocultural context would even help us be able to isolate sources of the cognitively-evoked components as well? One point that the authors make is that isolating the sources of components can be difficult, especially when a physical property is changed during the revision of a psychological property. The authors’ focus of this paper is simply to explain how stimulus presentation and ERP data is collected, so their lack of consideration for ERPs as a cost-effective neuroscientific method that may be used outside of psychology isn’t surprising. This leaves me wondering how anthropology’s current methods would be able to help us understand how ERP components work in a more complete way. The authors also mention that in order to be able to isolate ERP components, researchers need to describe in detail the physical characteristics and timing of the stimulus presentation as well as the participant is expected to do in response to the stimulus. These two descriptions could serve the anthropological community well in that descriptions and responses to stimuli are two things that ethnographic research does really well. One shortcoming may be in the careful timing of each stimulus presentation and the milliseconds afterwards when the ERP components are evoked. Overall, this article describes the basics of the ERP method very well using language that can be understood across disciplines. Although there may be many challenges when attempting to incorporate this particular method into anthropological and educational research, it may be worth it just to know more about ERPs and some of the principles behind the method. Tavakoli, P., & Campbell, K. (2015). The recording and quantification of event-related potentials: I. Stimulus presentation and data acquisition. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 11(2), 89–97. by Michelle BirdMankind has been plagued by questions of our origin from the beginning of time. Many different suggestions have been provided, but Falk argues that the intelligence inherent in modern primates is associated with changes that occurred over deep time, which consist of not only an increase in absolute brain size juxtaposed with a decrease in relative brain size (or RBS), but also asserts that the fluctuations in size alone are not enough to explain the amount of behavioral diversity observed among primates. She proposes that a sort of reorganization of the brain occurred in regards to the composition of cranial circuitry, neurochemistry, and subsystems, which reassembled to accommodate evolutionary behavioral changes.

Falk captures her audience by describing a uniquely primate propensity towards curiosity, and explains the proposed origins of how humans came to be both the largest-brained and most intelligent species. She describes the first monumental changes as “shifts” from leading nocturnal, terrestrial lives to diurnal, arboreal ones, thus explaining our “enhanced visual ‘modules’” as opposed to those of the olfactory, and the increase in visual prominence that “led to improvements in sensory-motor coordination in conjunction with a variety of locomotor patterns that evolved in different arboreal species (Falk 1496). Following descriptions of established direct (studying fossilized endocasts) and indirect (comparative) methodologies in the field of paleoneurology, Falk introduces new methods that “have major implications for normal as well as diseased human brain function, employ more and more complex methods and reveal the workings of smaller brain components” (Falk 1499). Determining the true significance of primate brain size has been challenging, as Falk points out by describing the relationship between relative and absolute brain sizes. The absolute measure varies so greatly among living primates that comparison is virtually useless, but RBS presents its own issue of not accounting for allometric scaling that leads to a tendency to “[overestimate encephalization] for smaller-bodied species, but underestimated larger ones” (Falk 1502). In addition, this change in size does not account for the increase in intelligence observed among humans, for which Falk presents an explanation of the evolution of neurological reorganization. She states that early primate evolutionary trends included not only increased brain-to-body size ratios but also increases in the relative sizes of the neocortices and the amount of visual cortex, a decrease in the size of olfactory bulbs, and the development of a central rather than coronal sulcus in anthropoids (Falk 1509). This information paired with a comparative study of cortical specializations that showed evolution occurring independently in both New and Old world monkeys as well as the retention of similarities from a common ancestor suggest that “the addition of new cortical areas may have provided an opportunity for the evolution of new behavioral capacities” (Falk 1510). She continues to describe how neurological reorganization has been evidenced to have occurred in the cerebellum through comparisons of the lateral cerebellar system among primates, which is described as “relatively large in chimpanzees and gibbons, while a central nucleus is larger in humans than in apes” but is smaller in humans that predicted (Falk 1510). The implication here is that an increase in size is not enough to explain all of the advances in motor coordination and cognitive thinking, and also that it is not necessary for a part of the brain to be “’new’ or grossly enlarged for reorganization to occur” which implies that these evolutionary advances may not have to be selected for by nature at all. There is also evidence that a complex social life could have influenced the selection for a larger brain, meaning the organization of human brains “is quantitatively different from any other living primate” and is not related to brain size alone. Another study has suggested that human cognitive ability, contrary to prior belief, has not “evolved in conjunction with differentially enlarged frontal lobes”, explained by quantifying the allometric nature of the human frontal lobe” (Falk 1514). Falk’s main purpose is to bring to light some of the lesser known intricacies that drive primate brain evolution and how they have influenced both neurological structure and function, and dispute the claims that alterations in brain size alone are enough to account for the variety of behaviors that occur across time among primates. She asserts that “arguments about the relative evolutionary merits of brain size versus neurological reorganization are unnecessary” and that “the sizes of different brain structures are a consequence of overall brain size” and not necessarily the result of a specific kind of trade-off (Falk 1517). For all of the unknowns concerning the origins of human brain evolution, Falk has clearly shown that the “high intelligence of today’s primates flowered from trends in primate brain evolution that reach back into deep time” and has effectively introduced the possibility that “neurological reorganization can take place with, or without, an increase in brain size” and suggests that because of this, there is “the potential for evolving internal functional interactions, loops, or modules” within the brain (Falk 1518). Falk, D., 2014. Evolution of the primate brain. Henke W., Tattersall I. Handbook of Paleoanthropology, continually updated edition, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. DOI: 10.1007/SpringerReference_135072 |

AuthorThis blog is group authored by Dr. DeCaro and the students in his ANT 474/574: Neuroanthropology. Archives

April 2019

Categories |

|

|

Accessibility | Equal Opportunity | UA Disclaimer | Site Disclaimer | Privacy | Copyright © 2020

The University of Alabama | Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 | (205) 348-6010 Website provided by the Center for Instructional Technology, Office of Information Technology |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed